Ahead of the upcoming revision of Colorado River conservation regulations by stakeholders in the U.S. West, experts are emphasizing the importance of including Mexico’s needs in the decision-making process from the outset.

The 1,450-mile waterway, running from the Rocky Mountains to the Sonoran Desert, serves as a vital resource for approximately 40 million people in both the United States and Mexico.

Policy advisors in the region emphasize that prioritizing cross-border investments could play a crucial role in ensuring stability in a basin that has been grappling with megadrought conditions both upstream and downstream for several years.

Carlos de la Parra, a water management and environmental policy advisor on the U.S.-Mexico border, highlights the importance of recognizing the reality of the Colorado River as one interconnected watershed. He emphasizes the need to carefully assess all costs involved and ensure an equitable distribution of resources between the two countries.

Last month, the Biden administration initiated the official process of revising the Colorado River’s Interim Guidelines for Lower Basin Shortages. These guidelines, set to expire by the end of 2026, determine the water conservation requirements and schedules for water users in the region.

While the outcome of these discussions could have a substantial impact on Mexico, it is essential to note that they primarily involve U.S. federal, state, and tribal entities. Despite Mexico’s entitlement to approximately 9 percent of the Colorado River’s total flow, its direct involvement in the talks is limited to the United States.

As the existing guidelines for the Colorado River approach their end, a separate binational agreement governing the joint management of the river by the U.S. and Mexico will also expire. This implies that while domestic conversations on the river’s management take place, there will also be international renegotiations between the U.S. and Mexico to address the river’s management collaboratively.

Yamilett Carrillo, senior manager of the San Diego Foundation’s Binational Resilience Initiative, commented:

“Every stakeholder in the basin holds significant leverage. With shared risks, it is crucial for everyone to contribute to finding solutions; otherwise, the consequences will affect all parties involved.”

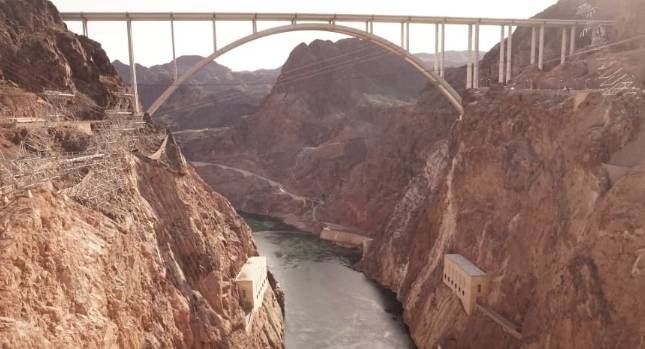

The Colorado River primarily flows through the U.S. before crossing into Mexico and gradually decreasing in volume just south of the international border, spanning the states of Sonora and Baja California.

In 1922, a compact was established that allocated 7.5 million acre-feet of water annually to each of two basins in the U.S. Subsequently, the Mexican Water Treaty of 1944 granted an additional 1.5 million acre-feet of water to Mexico. To put it into perspective, an average suburban U.S. household consumes about an acre-foot of water per year.

In the past, the Colorado River used to flow all the way to Mexico’s Gulf of California. However, nowadays, the river flow typically diminishes much closer to the border due to upstream withdrawals and diversions.

Instead of the historical flow to Mexico’s Gulf of California, Mexico’s annual allocation from the Colorado River is fulfilled through the Morelos Dam, located in the border area. The dam is jointly managed by the U.S. and Mexico through the International Boundary and Water Commission (IBWC or CILA in Mexico). The majority of the water passing through the dam is redirected to irrigate agriculture in the Mexicali Valley.

Jennifer Pitt, the Colorado River program director for the Audubon Society, says:

“The U.S. holds control over the water flow, essentially acting as the faucet. Mexico’s leaders have opted for a clear agreement specifying the quantities of water they will receive under various conditions, rather than leaving the decision solely in the hands of U.S. authorities. This approach ensures predictability and stability for Mexico’s water allocation.”

Shifting the conversation on conservation

Since 1944, the U.S. and Mexico have approved numerous IBWC decisions, referred to as “Minutes,” concerning their shared water resources. In recent years, two highly significant resolutions were enacted: Minute 319 in 2012 and Minute 323 in 2017, specifically addressing the management of the Colorado River.

The importance of collaboration between the two countries was underscored by these two agreements, serving as a testament to their value. Moreover, these bilateral conversations demonstrated the potential benefits they could bring to water users throughout the entire Colorado River basin.

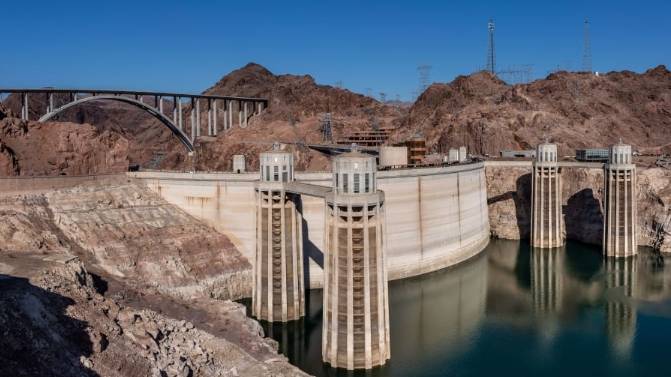

Minute 319 expanded on previous arrangements that permitted Mexico to defer its Colorado River allocation to address infrastructure damage caused by the 2010 El Mayor-Cucapah earthquake. In this agreement, the U.S. took on the responsibility of storing the deferred water supply in Lake Mead reservoir, while also establishing provisions for potential cuts that Mexico might face during times of water shortage.

The act of the U.S. offering Mexico necessary assistance in storing water, free of charge, served as a clear demonstration of the collaborative approach between the two nations, emphasizing that they are united in facing shared water challenges, according to Carrillo, who played a role as a scientific advisor in past negotiations.

Under the provisions of Minute 319, the U.S. additionally committed to releasing approximately 105,000 acre-feet of water into the Colorado River Delta during a two-month period in 2014, known as the “pulse flow.” This significant release revitalized wetlands and briefly allowed the waterway to flow all the way to the Gulf of California.

Minute 323, on the other hand, upheld Mexico’s capacity to store water in Lake Mead while also stipulating that the U.S. would invest $31.5 million in water efficiency projects in Mexico. Moreover, it established a work group to explore the possibility of creating a binational desalination plant in the region.

Minute 323 also featured a crucial provision in which Mexico committed to reducing its water consumption during periods of water shortage. However, this commitment would only be activated once the U.S. basin states had implemented their own reduction protocols.

The demand from Mexico represented a significant shift in the bilateral relationship, where the U.S. would often make assumptions about the other country’s conservation capabilities without involving its delegates in a collaborative process, as pointed out by Pitt.

Similar to both Minute 323 and the 2007 Interim Guidelines for Lower Basin Shortages, the state-level reduction protocols are also scheduled to expire in 2026, making it a pivotal year for Western water management.

The combined agreements led to the implementation of temporary conservation measures in both Mexico and the U.S. Lower Basin States—California, Arizona, and Nevada—during the summers of 2021 and 2022, in response to severe drought conditions.

Cross-border compensation for cutbacks

As delegates head to the negotiating table post-2026, experts acknowledge uncertainty about the exact outcomes. However, they remain confident that both countries recognize the mutual benefits of basin-wide conservation.

According to Peter Culp, a Phoenix-based attorney specializing in Colorado River law, there has been a significant history of stakeholder participation since the 2007 guidelines.

Mexican officials now expect to be involved in discussions from the beginning, and there are likely already private conversations happening in both countries, according to Carlos de la Parra.

Unlike the situation in 2007 when the parties were mainly addressing drought conditions, the upcoming negotiations in 2026 are driven by the realization that they are now dealing with the broader issue of climate change, according to Peter Culp, who has been involved in developing and supporting previous international agreements in the basin.

He questioned:

“What measures are needed to ensure the basin’s sustainability in the face of ongoing aridification, where conditions may deteriorate further in the future?”

For scholars and scientists across the region, the solution to this question, especially concerning Mexico, centers around agricultural conservation and the financial support required to revitalize a sector that yields minimal profits.

Upgrading irrigation practices among farmers in the Mexicali Valley, who rely on Colorado River water for their crops, has been challenging due to a lack of incentives and financial resources, as pointed out by de la Parra, the water expert on the U.S.-Mexico border.

De la Parra pointed out that the burden of water shortages is currently falling heavily on the agricultural community, which hasn’t needed to develop resilience over the past 75 years. As a result, there hasn’t been much incentive for them to build the ability to cope with water shortages.

De la Parra emphasized:

“Implementing enduring measures to combat drought would entail costly endeavors, such as upgrading infrastructure, optimizing land, enhancing efficiency, and modernizing irrigation districts. Unfortunately, these actions exceed Mexico’s current financial capacity”.

De la Parra pointed out that Mexico is in dire need of additional funding, but its financial resources do not match those seen in the Inflation Reduction Act, a significant climate-related provision found in the Biden administration’s 2022 spending bill.

According to an anonymous consultant closely involved with various Colorado River stakeholders, any significant investment in modernizing Mexicali Valley agriculture would need to be based on a compensation mechanism.

Supporting de la Parra’s views, the consultant suggested that the most effective approach would be to directly invest in agricultural land. They acknowledged the significant resource disparity and emphasized the shared responsibility of conservation efforts. Conservation in Mexico benefits system stability in the United States, just as it does in Mexico.

Taking this into consideration, experts proposed a potential agreement where the U.S. would invest in revitalizing Mexicali’s agricultural infrastructure and introducing farmers to higher-value, less water-intensive crops in exchange for Mexico’s commitment to conserve additional water. This mutual arrangement could create a win-win situation, addressing the region’s water challenges while supporting the modernization and resilience of Mexicali’s agricultural sector.

Pitt emphasized that for the U.S. to achieve a resilient outcome, it is in their best interest to assist with the transition in the Mexicali Valley by providing financial support for agricultural operations that can sustain value production with reduced water usage. By investing in this transition, both countries can work together to address water challenges and foster long-term sustainability in the region.

Culp added that achieving this transition is unlikely through private financing alone, as the economics are not conducive to supporting an independent transformation of agriculture to meet the challenges posed by a climate-challenged basin. Public investment and collaborative efforts between the two countries are essential to facilitate the necessary changes and ensure the region’s agricultural sustainability in the face of climate change.

“That leads to the inevitable conclusion that we must drive public investment towards it,” he said.

A river that flows ‘both ways’

Even with the U.S. directing funds towards revamping regional irrigation infrastructure, optimizing the flow of water to where it’s needed often demands flexibility and creativity among Colorado River users.

De la Parra presented a hypothetical scenario in which Arizona water authorities might consider “lining canals in the Mexicali Valley in exchange for a specified volume of water.”

According to de la Parra, this kind of swap has been seen before, as similar transactions were executed during both Minutes 319 and 323. Another potential option could involve the construction of a binational desalination facility, as explored in the study that followed Minute 323. Various locations, such as Mexico’s Pacific Ocean Coast or the Gulf of California’s Sea of Cortez, were considered in the report.

De la Parra highlighted the unique characteristic of the Colorado River, stating:

“The beauty of the Colorado River is that it can actually flow both ways.”

He expressed certainty that cities like San Diego or Los Angeles would be willing to invest in a desalination plant in exchange for a portion of Mexico’s Colorado River allocation. Although California and Baja California operate under distinct regulatory systems, sharing expenses related to land use, environmental impact, and energy would prove advantageous for the entire region, according to de la Parra.

Pitt expressed doubts about the comprehensive impact of a desalination facility on the Colorado River basin, but she acknowledged that it could significantly alter the power dynamic between the US and Mexico concerning control over water supplies.

However, she cautioned that this project should not be seen as a cure-all solution, as it alone would not fully address the supply-demand gap in the region. Additionally, implementing such an energy-intensive facility would necessitate finding a new power source and undergoing the necessary permitting processes, according to Pitt.

Apart from the crucial water supply and augmentation aspects, Pitt emphasized that she would encourage delegates to contemplate specific environmental measures during the bilateral negotiations. These issues might encompass ecological restoration initiatives or a heightened focus on addressing the salinity problem that occasionally affects the water flowing from the U.S. into Mexico.

Carrillo, on the other hand, stresses the importance of taking into account basin-wide conservation strategies, which should include consideration of the Tijuana River watershed. This region has effectively become a terminus for the flow of the Colorado River.

Even though Tijuana is not geographically close to the river, it receives a portion of Mexico’s Colorado River allocation through an aqueduct that traverses the Mexicali Valley, making it one of the most downstream municipalities in the basin. Additionally, the city can access Colorado River water from California during emergencies.

Carrillo emphasized that considering the Tijuana River as a completely separate watershed from the Colorado River is a misconception and a significant mistake. In reality, the two waterways are interconnected, and their management requires coordinated efforts.

Carrillo advocated for including the Tijuana River watershed in the binational Colorado River negotiations, citing opportunities to promote water conservation through investments in sewage treatment and related infrastructure in the area. By addressing water management issues in Tijuana, the overall conservation efforts in the Colorado River basin could be significantly enhanced.

De la Parra concurred with Carrillo’s perspective, describing Tijuana as potentially “artificially” being considered the endpoint of the Colorado River. However, he emphasized a crucial point, noting that Tijuana’s water usage accounts for only about 15 percent of the region’s overall consumption, while the remaining 85 percent is utilized for agricultural purposes.

De la Parra suggested shifting the focus on water scarcity, management, and improvement towards the agricultural community first and then towards cities as a secondary consideration.

Reshaping a bilateral narrative

Culp emphasized the significance of developing a shared basin-wide narrative that highlights collaborative efforts between the U.S. and Mexico alongside the crucial role investments will play in the next round of talks.

Carrillo emphasized that shaping the narrative for the next round of talks would require a commitment to transparency and sharing information with the general public. According to her, sharing plans, scenarios, assessments, and comparisons openly will be vital in crafting a new story for the future of the Colorado River basin.

Citing the strong connections between families on both sides of the border in the Colorado River Delta region, Carrillo emphasized the abundance of goodwill present in the negotiations.

Pitt also shared her enthusiasm for the renegotiation process, acknowledging its complexity while highlighting the solid history that has been built over the past decade. Despite the challenges, both experts are optimistic about the potential for constructive and impactful outcomes.

According to Carrillo, the U.S. and Mexico’s relationship regarding Colorado River management has undergone a remarkable transformation. She expresses optimism and believes that another positive agreement will be reached in the negotiations. De la Parra also shares the sentiment of optimism and dismisses claims that future conflicts will be over water, considering them entirely unfounded. Both experts share a positive outlook for the future of the Colorado River basin.

De la Parra highlights that data and historical trends do not support the notion of future water conflicts. He points out that there have been more agreements on water management than disputes, indicating a positive track record in resolving water-related issues between nations.